The past 18 months have put a once in a lifetime level of pressure on the world. The COVID-19 pandemic has provoked a global health crisis, disrupted global food systems, and reversed years of progress on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The future of the world depends on good food. Good food keeps us healthy, it helps us reach our potential, it strengthens our communities, powers our economies and protects our planet.

COVID-19 is estimated to have dramatically increased the number of people facing food insecurity, with the World Food Programme estimating that 272 million people are already or are at risk of becoming food insecure. Even before the pandemic, millions of people were unable to access good food due to economic, financial, geographical, climatic, cultural, social and political factors.

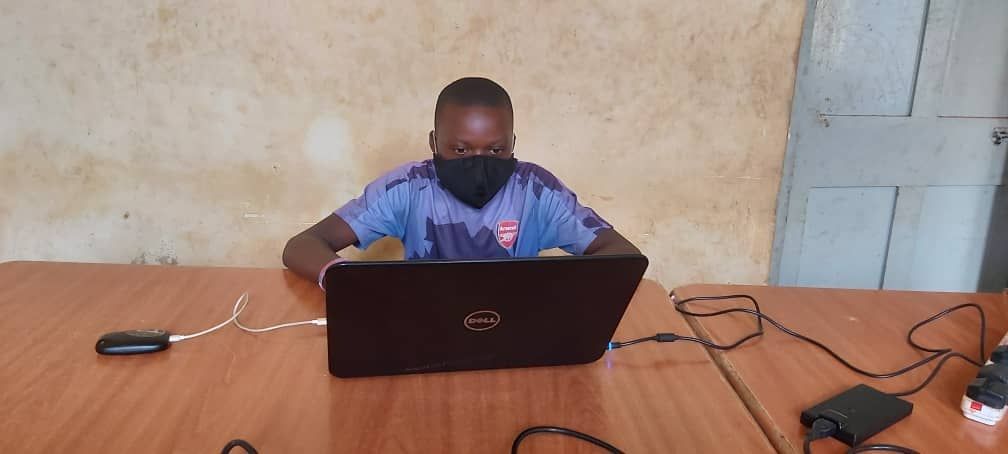

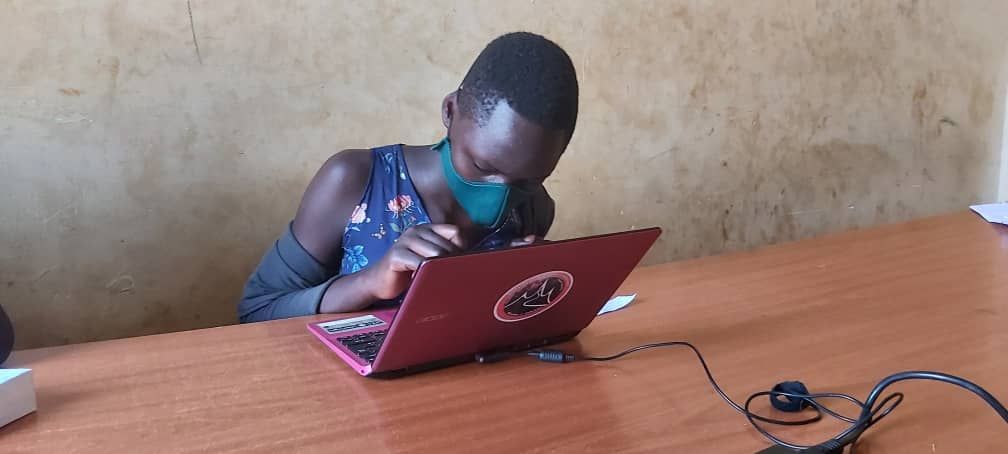

So, this month the young people S.A.L.V.E works with asked our global supporter base whether the solution to world hunger lies in changing the way we farm.

Agnes in Uganda highlighted the role of climate change and environmental degradation, arguing that we need to grow crops that are resistant to diseases and mature fast. This intervention is particularly relevant as this week global leaders, businesses, advocates and affected communities attend the UN Climate Change Conference, or COP26.

In an intervention that has since gone viral, Sir David Attenborough spoke at COP26, arguing that a new industrial revolution – powered by millions of sustainable innovations – is essential, and indeed already beginning.

Our debaters highlighted some of the innovations that Sir Attenborough referred to, talking about climate change resistant crops, hydroponics, sustainable resource management, biofuels and irrigation strategies.

Nicola in the UK pointed how, however, that there is no single answer to world hunger.

“I think a lot of it comes down to our unequal societies and food systems which allows some people to be hungry when there is enough food globally available for everyone to eat.”

This theme of greed and over consumption by rich countries was a thread that ran throughout the debate. For example, Ajay stressed that tackling greed and corruption, as opposed to rehauling farming systems, is the real solution to ending world hunger.

Leigh in the UK pointed out, however, that even within rich countries, there are still populations that are unable to afford safe and nutritious diets, highlighting that wealth disparity and domestic poverty have a significant impact on people’s ability to buy food in the UK.

The debate also touched on the critical issue of food loss and waste

One guest – contributing under the dynamic name Guest Man of the Moment! – raised the issue of food waste. He argued that reducing food waste would mean less inputs are used in food production, including fertilisers, land, machinery etc. Whilst, they argued, this would have a direct positive impact on climate change resilience, methods of reducing food waste – including post-harvest management – also come with risks to the climate. How then, they asked, do we reduce food waste?

Students joining from Woodhaven School argued that one way to do this was to tackle the way we eat, as opposed to the way we farm, writing that some countries overconsume and produce waste, whilst others suffer high rates of hunger. “If richer countries took less and wasted less, there would be more to go around.”

Several other debates highlighted how changing what we eat could have an impact on productivity and consumption habits. One participant pointed to vegetarianism as a helpful solution, highlighting the increased efficiency of using land for human-edible crops, as opposed to growing food to feed animals ahead of slaughter.

There is a livelihood element to consider with this argument, however. Over one billion people work in the agricultural sector, and their interests must be considered when proposing solutions around world farming systems. If one type of farming is to be reduced, will they be retrained and given opportunities to change to another more sustainable type of farming? Ruth and Nat argued, “Farmers need to be supported and protected particularly with volatile pricing and unpredictable weather…We also need to be addressing food waste, changing climates, capitalism, over production, and consumerism.”

Other people highlighted wider issues that impact world hunger. Edrine in Uganda pointed to the crucial impact of ending or responding to forced migration, highlighting that “refugees are the most vulnerable groups when it comes to hunger and they can hardly have land to carry out farming for survival.”

This month’s debate gave rise to some really interesting interactions and we want to say a huge thank you to all of you who joined us for such a lively debate.

If you found this article interesting, please take part in next month’s debate. You can contribute throughout the month or by joining live on the 25th of November: Will the actions we take today be enough to limit the effects of climate change? Or is it too little too late?

To read more about S.A.L.V.E and the work we do in Uganda, take a further look at our website here.

NB: The website platform that we use for the online discussion is designed to be child safe, ensuring that no one can get each other’s contact details and our team carefully moderate the content shared.

0 Comments